A new study sheds light on how parental behaviors modulate infants’ processing of affective (soothing) touch. The research indicates that infants tend to have a greater brain response to touch when their mothers are less sensitive to their signals and needs. The findings have been published in Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience.

“Touch is essential to the establishment of affective bonds and to a person’s well-being,” said study author Ana Osório, an assistant professor at the Center for Biological and Health Sciences at Mackenzie Presbyterian University in Brazil.

“The interpersonal touch experience is particularly important in early childhood since it is the most fundamental form of parental care. However, the study of this sensory modality remains surprisingly neglected. We wanted to know whether the way mothers care for their infants — how warm and attentive they are to their child’s needs — impacts how infants’ brains process affective, gentle touch.”

The study included 24 infants and their mothers. When the infants were 7 months old, the mothers were instructed to play with them for 9 minutes. “We watched them interact with their infants and assessed maternal sensitivity — how well they acknowledged the infant’s needs and communications, interpreted them correctly and provided a contingent and appropriate response — for instance, holding the child when upset or afraid,” Osório said.

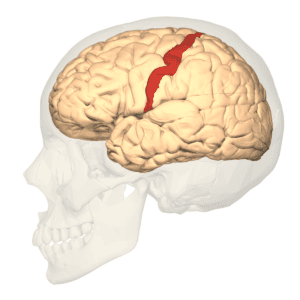

The infants underwent brain scans when they were 12 months old. To simulate affective touch, the infants were slowly stroked with a watercolor brush. “We looked at how their brains reacted to gentle touch using a technique called fNIRS (functional near-infrared spectroscopy). fNIRS uses near-infrared light to detect changes in brain tissue oxygenation,” Osório explained.

Osório and her colleagues found increased brain responses to affective touch in the somatosensory cortex among infants whose mothers were less sensitive.

“We found that when mothers were less sensitive, their infant’s brains actually showed stronger activation patterns in areas that process touch,” Osório told PsyPost. “It can be hypothesized that infants exposed to less sensitive maternal interactions – in which maternal touch might be absent, inconsistent, non-contingent and non-attuned to the infants’ cues and signals – may have perceived the light touch received during the fNIRS task as more novel, thus engaging in increased neural processing of the stimulus’ characteristics and meaning.”

But the study — like all research — includes some limitations.

“We did not have a measure of maternal touch, but a more general index of maternal sensitivity (which includes touch, but also other types of behaviors),” Osório explained. “Future research may explore the links between frequency, type and contingency of maternal touch during mother–infant interactions and infants’ brain responses to gentle touch to clarify how everyday touch experiences modulate brain responses to this sensory input.”

The study, “Maternal sensitivity and infant neural response to touch: an fNIRS study“, was authored by Vera Mateus, Ana Osório, Helga O Miguel, Sara Cruz, and Adriana Sampaio.